By Lara Okunoren (she/her)

Content warning: discussion of racism, misogyny

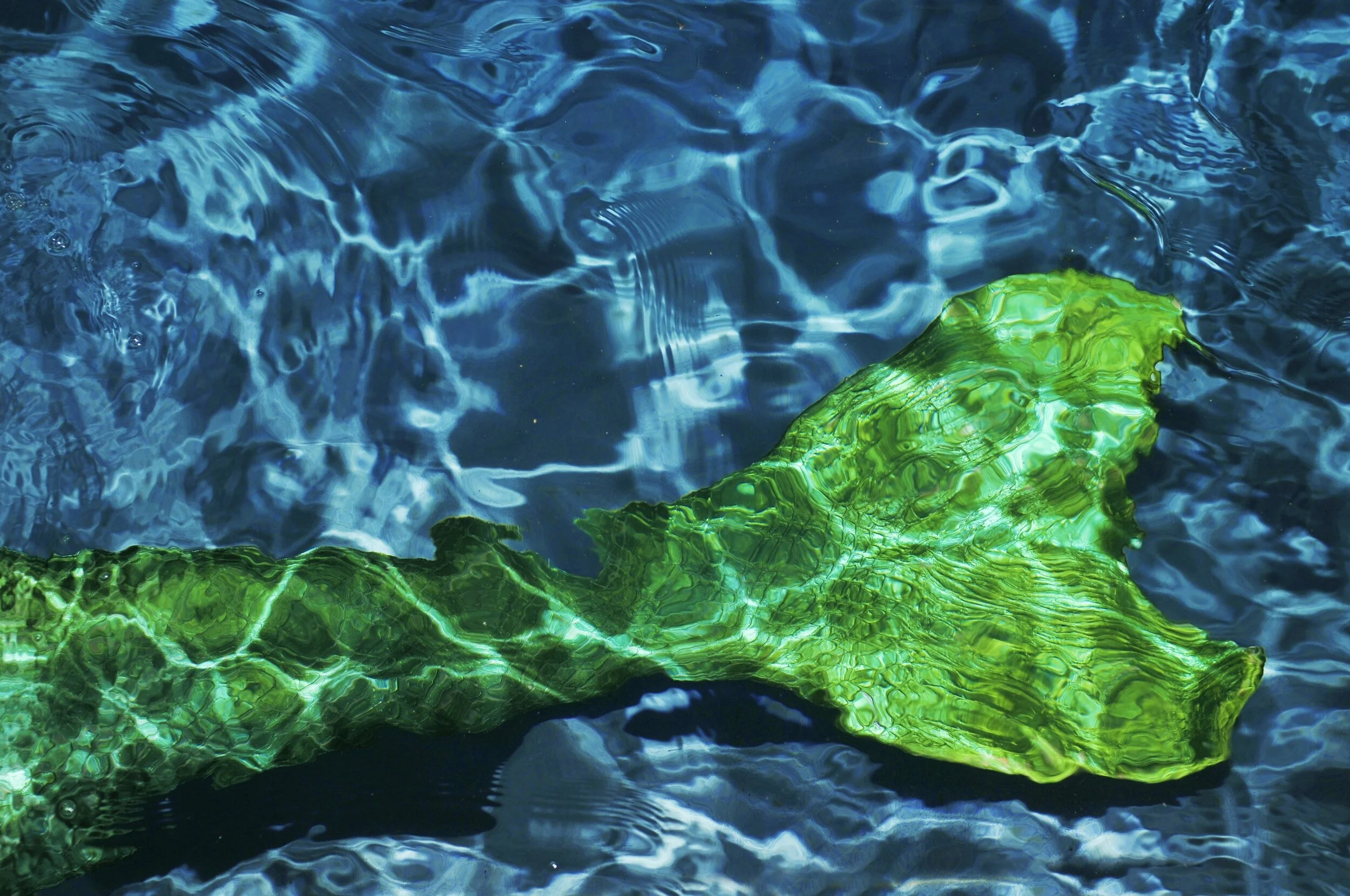

In May 2016, Disney announced a live-action adaptation of “The Little Mermaid” fairy-tale by Hans Christian Andersen. There were criticisms about the excessive live-action Disney adaptations because some argued that they are pointless cash grabs or fail to capture the nostalgia of animated Disney movies. However, there was general excitement from an array of individuals. Live-action Disney films have largely been critical and financial successes, portraying new and exciting interpretations of the animated versions that various age groups have enjoyed and appreciated.

In July 2019, the announcement of Halle Bailey as the leading role, Ariel, garnered a mixture of responses. Western media has a long history of racism, sexism, and other forms of institutional and systemic discrimination against marginalised groups. There were positive reactions to the diverse casting of Halle Bailey because it highlighted a step forward in the discriminatory industry towards more leading roles for individuals from marginalised backgrounds - roles without reinforcing negative, prejudiced controlling stereotypes. Moreover, young black girls finally had another Disney princess, who “looked just like them” as many said in viral Tik Tok videos. Princess Tiana from “The Princess and the Frog” was the only black princess character in Disney’s long history of 99 years. Halle Bailey received support from established actors, celebrities and more, such as Jodi Benson, the actress who voiced Ariel in the 1989 animated version.

Yet, the negative backlash prevailed over the positive feedback, creating an online echo chamber of hate and misogynoir towards Halle Bailey. A global, online hashtag, “#not my ariel,” trended on various social media platforms with objections over the casting. On September 10th, 2022, Walt Disney Studios released a trailer for the film on YouTube that amassed an overwhelming (approximately) 1.5 million dislikes within two days. There were many misogynoir and body-shaming hate comments directed towards Halle Bailey. Although Misogynoir is a term coined by Moya Bailey in 2010, it has a long history with black feminist thoughts and theory. Misogynoir is the combination of racial and misogynistic discrimination directed at black women. It is often overlooked as black women’s oppression and issues have been viewed one-dimensionally - either as a race or gender issue. Therefore, Intersectional and black feminists have established the importance of an intersectional perspective towards social issues and identities because “there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives” (Audre Lorde, 1982).

Various criticisms were directed towards the casting of Ariel, such as the lack of historical accuracy and faithfulness to the original fairy-tale, political correctness, and the race change of Ariel and her natural ginger hair (also known colloquially as Ginger-Washing). Race-changing of characters, also known as race-bending, is controversial. It has a long history of whitewashing, reinforcing racial stereotypes and depictions of ethnic minorities and denying actors of colour roles in favour of white actors. There have been mixed responses from society on the race-swapping of white characters to ethnic minority characters. On the more critical (neo-liberal) spectrum, some argue that this emphasis on “wokeness” and political correctness in media is damaging as identity politics creates hierarchies of oppression - in which certain social groups are prioritised and favoured due to their marginalisation.

However, some argue that race-changing white characters to people of colour is not progressive and practical for real diversity and representation because it highlights the laziness of Western media to create new non-white characters. Therefore, people of colour can be empowered through new and exciting projects that are created solely for them. For example, in recent times, Jordan Peele’s filmmaking of horror movies with a predominantly black cast has been highly praised by black communities as he creates new black characters that reject racist and other intersecting stereotypes while creating positive representation and space for black audiences to be heard and empowered.

The concept of Ginger-washing is that iconic red-haired characters in media are being replaced by non-red-haired actors. This is significant as only around 2% of the world’s population have natural red hair so the portrayal of red-haired characters by non-red-haired actors threatens natural ginger representation. For example, Mary Jane in the “Marvel Cinematic Universe,” Starfire in “Titans” and Josie Mccoy in “Riverdale.” However, a major inconsistency of ginger-washing is the claim of protecting and preventing the erasure of natural ginger-haired characters, but it does not take issue with white, non-natural red-haired actors portraying ginger-haired characters. For example, Sophie Turner, who portrayed Sansa Stark in “Game of Thrones” & Scarlett Johansson, who portrayed Natasha Romanoff in the “Marvel Cinematic Universe,” are natural blondes, who dyed their hair or wore wigs for their roles. Therefore, the ideology of ginger-washing is used as an (online) dog whistle to evoke racial abuse and discrimination against actors of colour with the justification that red-haired individuals are losing representation. Despite Halle Bailey’s portrayal of Ariel with red hair, critics claimed it was not “red enough” and did not showcase the 1989’s version of Ariel’s iconic “fire-truck” red hair. Thus, much of the criticisms against the casting of Ariel were rooted in misogynoir, hidden through dog whistles such as ginger-washing.

Despite negative responses and hate-bombed reviews, “The Little Mermaid (2023)” garnered positive reviews from audiences and critics. It is currently the seventh-highest-grossing film of 2023. Many praised Halle Bailey and perceived it as her breakthrough role due to her powerful vocals and acting portraying an insightful interpretation of Ariel. However, Halle Bailey continues to be plagued by hate trolls on social media. Some hate comments attempt to diminish her talent by claiming her co-star, Jessica Alexander, who portrays Vanessa as Ursula’s human alter-ego, “looks more like Ariel'' and “sings better than Halle.” The irony is that Halle Bailey sings for both Ariel and Vanessa in the movie & Jessica Alexander is not a natural redhead. This further highlights how the negativity that Halle Bailey has received is rooted in racism as her blackness is pathologised. Society's normalisation of misogynoir is used as a covert mechanism to discredit and belittle Halle’s talent, individuals turning a blind eye to Halle’s talent for the sake of perpetuating misogynoir.

Other than a statement that defended Halle Bailey issued by Freeform, a Disney-owned cable network, Disney and its other services remained silent on the misogynoir and hate train that afflicted Halle Bailey. Cast and production members, such as Lin-Manuel Miranda who produced and co-wrote songs for the movie, spoke out and defended the casting of Ariel. However, Disney’s silence and lack of measures to protect Halle emphasise how companies claim to be progressive and accepting of diversity but fail to protect their actors of colour. As Candice Patton (Patton plays Iris West in CW’s The Flash) said in “The Open-Up Podcast,” companies fail to address misogynoir attacks that black actresses face and “put them in the ocean, alone with sharks” to face bullying and harassment without any support or protective measures. Therefore, companies need to impose effective measures to protect their actors of colour from abuse and online hatred as society is infused with intersecting discriminations that attempt to create barriers and oppress marginalised communities. Companies must hold themselves accountable and advocate for diversity that promotes and protects both the characters and actors.

Reactions from society about the little mermaid highlight that diversity and representation are tremendously needed in media, especially in neo-liberal Western societies that claim social oppressions no longer exist in post-racial, post-misogynistic and other post-discriminatory societies. “The Little Mermaid (2023)” is loosely based on the original book, intending to incorporate more modern themes to reflect society’s current social context and changes. Although some critics point out that there should be more original projects created for women and actors of colour instead of hand-me-down roles, the hate Halle Bailey received was rooted in misogynoir, masked in the protection of historical accuracy, faithfulness to the original fairy-tale and natural red-hair representation.

Why can’t black people play mermaids or princesses without the hassle of racist internet trolls? It is time for Hollywood (and Western media in general) to be brave enough to introduce more stories and roles for actors of different backgrounds to be able to represent positively, resist roles with negatively controlling images and access more leading roles. Black female actresses have attempted to portray diverse characters and create self-defined images to fight against discriminatory, stereotypical concepts perpetuated to normalise misogynoir. Halle Bailey as a black princess is a huge step forward, providing representation for many that are direly needed in our deep-rooted oppressive and discriminatory society.

REFERENCES:

Bailey, M. “Introduction: What Is Misogynoir?” Misogynoir Transformed, 25 May 2021, pp. 1–34, doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479803392.003.0004, https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479803392.003.0004. Accessed 7 May 2023.

Bero, T. (2023). The global backlash against The Little Mermaid proves why we needed a Black Ariel. The Guardian. [online] 9 Jun. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/09/the-little-mermaid-global-backlash-black-ariel [Accessed 15 Jun. 2023]

Brown, R. N. (2013). Hear Our Truths. Baltimore: University of Illinois Press. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.5406/j.ctt3fh5xc.

Campbell, C. (2017). The Routledge companion to media and race / edited by Christopher P. Campbell. New York : Routledge.

Cheu, J. (2013). Diversity in Disney films : critical essays on race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and disability / edited by Johnson Cheu. Jefferson, North Carolina : McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Collins, Hill P, and Bilge, S. (2016) Intersectionality, Polity Press

Collins, Hill P. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 2nd ed., New York, Routledge, 1990, www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/252.html. Accessed 7 May 2023.

Davis, A.Y. (1981). Women, race and class. New York: Random House.

Esther, E, Marcia Texler Segal M.T and Lin, T. (2011). Analyzing gender, intersectionality, and multiple inequalities : global-transnational and local contexts. Bingley: Emerald.

Field, C. T. et al. (2016). The History of Black Girlhood: Recent Innovations and Future Directions. Journal of the history of childhood and youth, 9 (3), pp.383–401. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.1353/hcy.2016.0067.

Jean, E.A., Neal-Barnett, A. & Stadulis, R. How We See Us: An Examination of Factors Shaping the Appraisal of Stereotypical Media Images of Black Women among Black Adolescent Girls. Sex Roles 86, 334–345 (2022).

King, J. et al. (2021). Representing race: the race spectrum subjectivity of diversity in film. Ethnic and racial studies, 44 (2), pp.334–351. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1740290.

Heritage, S. (2022). We are all losers in the ‘woke v racist’ Little Mermaid culture war. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/sep/15/little-mermaid-disney-trailer-culture-war-ariel-black-white [Accessed 15 Jun. 2023].

Hooks, b. (2015). Ain't I a woman : Black women and feminism / bell hooks. [Second edition]. New York : Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Hooks, b. (2015). Black Looks. London: Routledge. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.4324/9781315743226.

Hull, A. G. et al. (2015). All the women are white, all the blacks are men, but some of us are brave : black women's studies / edited by Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott & Barbara Smith ; new afterword by Brittney Cooper. 2nd edition. New York : Feminist Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider : essays and speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press.

Mahdawi, A. (2022). Little Mermaid’s Racist Critics Pollute Magical Undersea World with Bigotry | Arwa Mahdawi. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/sep/17/little-mermaid-racist-critics-backlash [Accessed 15 Jun. 2023].

Nwonka, C. J. and Malik, S. (2018). Cultural discourses and practices of institutionalised diversity in the UK film sector: ‘Just get something black made’ The Sociological review (Keele), 66 (6), pp.1111–1127. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.1177/0038026118774183.

Nwonka, C. J. (2021). Diversity and data: an ontology of race and ethnicity in the British Film Institute’s Diversity Standards. Media, culture & society, 43 (3), pp.460–479. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.1177/0163443720960926.

Scharrer, E., Ramasubramanian, S. and Banjo, O. (2022). Media, Diversity, and Representation in the U.S.: A Review of the Quantitative Research Literature on Media Content and Effects. Journal of broadcasting & electronic media, 66 (4), pp.723–749. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.1080/08838151.2022.2138890.

Shoard, C. (2023). The Little Mermaid subjected to ‘review bombing’ with mass negative reactions posted by bots. The Guardian. [online] 1 Jun. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/jun/01/the-little-mermaid-subjected-to-review-bombing-with-mass-negative-reactions-posted-by-bots [Accessed 15 Jun. 2023].

Sinwell, S. (2022). Teaching diversity, questioning representation. Alphaville, (24), pp.153–159. [Online]. Available at: doi:10.33178/alpha.24.10.

Robin Means Coleman (2011) “Roll up your sleeves!”, Feminist Media

Robin Means Coleman (2011) “Roll up your sleeves!”, Feminist Media Studies, 11:1, 35-41, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2011.537023

Rachel Alicia Griffin (2014) Pushing into Precious: Black Women, Media Representation, and the Glare of the White Supremacist Capitalist Patriarchal Gaze, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 31:3, 182-197, DOI: 10.1080/15295036.2013.849354