Below is an expanded excerpt from our latest advocacy eBook on ecofeminism, by Ishara Sahama.

For a long time, I’ve had some internal conflicts over the environmentalism movement, the socio-political agenda of living sustainably and how we must completely change our lives for the sake of saving our world from the climate crisis. That’s a lot to accept, comprehend and enact on as a 21 year old. So I can, at the very least, empathise with those who feel overwhelmed or lost when our political representatives (the few good ones), teachers, youth leaders, social enterprise networks and the media inform us on what we must do to curb our impact on nature and vulnerable communities. We’re constantly bombarded with online materials, public forums, media coverage and social movements revolving around topics of sustainable living, sustainable development and/or sustainability.

Source: Upsplash

But what is it exactly? How, in this day and age of a climate crisis, do we ‘live’ sustainability and empower others to follow value-led, holistic principles of living to meet your needs rather than your wants? More importantly, are we missing crucial information and understandings on sustainable living and development? Are we just operating in a limited pool of knowledge based on our unique identities or on something as simple as where we live?

So many questions! Maybe you have the same questions too. So let’s break it down.

Sustainability is a trigger word on social media, mainstream media and in the corporate world nowadays and because of that, its actual meaning is often lost and misconstrued.

Sustainability, at its core, is the ability to continue a defined behaviour or action indefinitely, or at least at a rate at which all concerned parties are able to live/function harmoniously. This doesn’t really mean anything until you bring in its three pillars: environmental, economic and social, and tie it to one of the most famous and well-recognized scholastic definitions of sustainability or sustainable development: “development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (UN Documents, n.d.). When considering sustainability in this context, it means that:

Environmental sustainability is about maintaining Earth’s environmental systems and biota; that they are balanced and any natural resources that must be consumed are able to replenish themselves naturally

Economic sustainability is about how economic systems are available and equitable to everyone in order to secure financial needs and ability to pay for a range of services and goods

Social sustainability is about ensuring people are kind and just to one another and within communities and that are people are protected from injustices, discrimination and exclusion. It also means acknowledgement and incorporation of universal human rights in all aspects of people-to-people interaction where everyone has equal and equitable access to enough resources to live healthily and securely

As such, sustainability is a big concept and is most often seen as a value that can be embedded into systems or followed by individuals or groups. The motivations behind following sustainable practice is therefore different, personal and complex. But in order to be sustainable, i.e. environmentally conscious of their actions and purchases, that action in it of itself means that the individual is able to make a conscious decision, has the time and financial and/or social freedom to follow that pathway. This person may be someone who lives in a metropolitan area, studies at university or maybe even works in a government firm, and is living alone or with support from housemates or family. Whilst this is just an example, the individuals or communities who are able to make the effort to switch to sustainable lifestyles and consider where they get their food from, how they source energy to their household, where their clothes come from and who makes them, which Super investment fund they’ll choose and what mode of transport they’ll use, are those who are typically living in urbanized regions where they have both the social and political freedom as well as the financial freedom and support to make such decisions. These sub-populations are mainly those who hail from middle class incomes and higher and live in regions where political environments follow democratic principles. But not everyone has the privilege to make environmentally conscious decisions or be able to make the decision to switch from a Toyota Camry to a Tesla.

Moreover, this is just an example of a Global North cosmopolitan perspective in urban environments where social movements of environmentalism and sustainability are often instigated by groups that don’t face discrimination and marginalisation.

Living holistically, sustainably and with cultural competency has been followed for thousands of years by the Indigenous custodians of this land (Australia). Our modern-day proclamations of ‘harmoniously’ living with nature on the media, especially on social media and influencers of the like, is not new news. The Indigenous people, of all nations, are the only cultural groups who have preserved the natural state of the world for centuries. They are, as Garnett et al (2018) says, the people [who] hold the future of much of the world’s wilderness in their hands and are crucial for conservation. Their deep connection to the lands and, in the context of Indigenous Australians, the passing of stories and practices of conservation, natural resource/prey tracking and a deep understanding of appreciating the Earth, have resulted in pristine preservation of land and ecosystems. As such, sustainability, in all intents and purposes of acknowledging, including and practicing processes which preserve the natural conditions of things, is Indigenous. In that same note, sustainability is Brown. Sustainability is Black. Sustainability is Asian. Sustainability is diverse.

Nowadays however, sustainability, living eco-friendly or trying to practice sustainable development practices in developed nations like Australia, has transformed into a “industry that is still designed by a bunch of privileged white people” (Radin, 2019). We almost never see Indigenous acknowledgements on our media of sustainable practice and inclusion of their perspectives in sustainable development and urban planning decisions. If in the off-chance we do, they’re often short, heavily edited snippets of conversation. So unfortunately, “sustainability is mostly being addressed by those who are reaping the benefits of privilege” (Radin, 2019).

So, what exactly are the issues between privilege and sustainability?

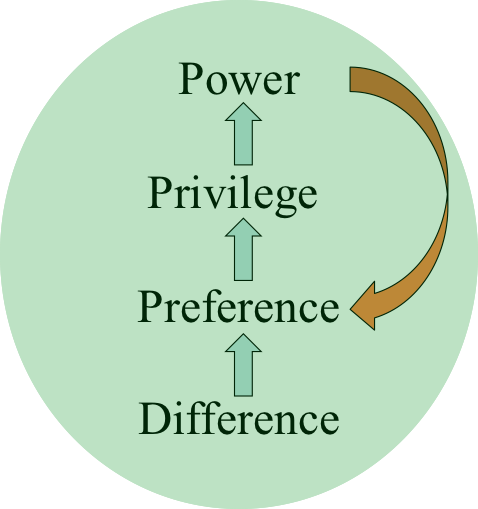

First and foremost is that sustainability practitioners and professionals, who in their own right are completing amazing projects which focus on solving multilateral environmental problems and social problems, often ignore the “systematic implications of privilege and power in their strategy development” (Kolan and Sullivan, 2014). What becomes even more problematic is when this lens of looking and implementing sustainability strategies are integrated into sustainability education programs and courses which fail to include analyses of power relations, privilege and cultural competency (Kolan and Sullivan, 2014). This means that if, for example, a practitioner or even an individual who took the time to educate themselves on socio-environmental issues such as fast fashion, went to empower their peers and enact the positive community change they envision, there might be a chance that their strategies of communication and empowerment are excluding more disadvantaged sub-populations and only giving value to those who are also equally able to attend/participate in community sessions. The social value of enacting change and providing community-based solutions to an issue is given to those who typically fit the dominant demographic and limited wider circle of those who share the same interests as the influencer/practitioner. As such, this social value creates a ‘margin dynamic’ (Kolan and Sullivan, 2014) whereby the individuals who want to enact on a dimension of difference to how, for example, clothes are brought and consumed. From there, they then create situations and followings where there is a mainstream group who share the same level of privilege as them. This is known as ‘unearned privilege’ and overtime, it provides more opportunity for said individuals to acquire power, otherwise known as social capital, to influence and control the community-values of a system, organisation or even social structure. This leads to a negative feedback loop of power intersecting with preference and privilege and, where differences are minimised and oppressed (figure 1) (Kolan and Sullivan, 2014).

The complexities of unearned privilege and its influence over communities through an individual or a small group who have the same shared preferences is influenced by multiple forms of difference and is often referred to as intersectionality (Kolan and Sullivan, 2014). Oftentimes, this unearned privilege of individuals is unconsciously supporting and reinforcing the status quo however, there is a way to engage difference, privilege and power and practice it differently. One way is for individuals who have a certain air of privilege and power is to give centre-stage to those who are usually oppressed or marginalised. This could be by simply giving individuals who tend to not have the public stage/arena as a place of general influence, a place to open conversation for their struggles and perspectives. Or it could be by listening more to the community, rather than advocating for change and action as a first line of reaction. By doing so, at certain times, it’s suitable to use one’s own power to reinforce the status quo, interrupt the cycle of oppression and minimize norms and structures which can reinforce unearned privilege (Kolan and Sullivan, 2014).

When practicing sustainability and engaging others on how to be more socially conscious, environmentally friendly or economically sensitive to changes in policy or industry-based decisions, it’s important to listen first to those affected and then consciously choose whether to use your own power and privilege to provide a voice for others, empower others or actively challenge norms and prejudices in systems. As an individual who studies the human interactions with the environment and society (Geography), is a student advocate, social justice activist and community organiser, I know firsthand how powerful and necessary it is to listen first and then make informed decisions to empower and include others for change. How we live sustainably falls of course to our own levels of privilege and accessibility, but we all have the ability to either voice or write our acknowledgement(s) of the Indigenous custodians of this land who have preserved and continue to preserve the environment, and their culture and social relations sustainably. This is the first step we must all take. From there, I would say the single most effective next step you can take is, as Jason Momoa, Jane Goodall, Xiuhtezcatl Roske-Martinez, Xiye Bastida, Autumn Peltier, Marinel Ubaldo and Greta Thunburg say:

“listen to the science”

“speak on behalf of the vulnerable and the marginalised communities”

“use your voice to make all our voices be heard”.

So, as an individual who studies our human interactions with the environment and society, I implore you to acknowledge your power, your privilege, read the science and above all, use your voice to include and empower others.

References

Garnett et al., (2018). Indigenous peoples are crucial for conservation – a quarter of all land in their hands. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/indigenous-peoples-are-crucial-for-conservation-a-quarter-of-all-land-is-in-their-hands-99742.

Kolan and Sullivan (2014), Privilege as Practice: A Framework for Engaging with Sustainability, Diversity, Privilege and Power. Retrieved from http://www.susted.com/wordpress/content/privilege-as-practice-a-framework-for-engaging-with-sustainability-diversity-privilege-and-power_2014_12/

Radin (2019). What the sustainable movement is missing about privilege. I-D Vice. Retrieved from https://i-d.vice.com/en_au/article/vb9ppd/what-the-sustainable-movement-is-missing-about-privilege

UN Documents. n.d. , Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, Retrieved from http://www.un-documents. net/ocf-02.htm